by Simon Cropp

In Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, we are told stories of the histories of people under the terminology of root canals. The important formation of who characters are in this novel, such as Archie and Samad, Irie, and Clara, is linked to the metaphor of teeth and how possibly the procedure of removing decay from the roots of their heritage.

Allow me a digression:

And this reminds me of my own uprooting, when my wisdom teeth had to be removed. Wisdom teeth are the last sets of teeth to grow in, and they’re often impacted, so later in life, almost all of us have to have the dreaded procedure.

I was 22 years old and didn’t have insurance that covered procedures;, so for me, the removal of wisdom teeth had to be a budgetary affair. My dentist said he knew a guy. Oral surgeon in training. Had to get a number of contact hours in to meet the requirements of his program, and removing wisdom teeth was considered something he could do unsupervised. I remember there was a rule he had to follow: no an anesthesia. I had to be awake for the procedure. But people do it this way I was told. He’d give me a Valium, I’d feel like I was asleep, all would be right in the world.

I showed up for the day of the procedure with my friend Mike–as the Valium would render me likely incapable of driving. I remember now, the receptionist at the dental office had captured my withered, blackened heart at that time. She would look at me with these big blue eyes, smile, and I never heard a thing she said. Well, when I checked in, she said something like: “The doctor is running late. Run and get something to eat. Blue eyes, beautiful smile, blue eyes,” or something like that.

Mike took me to McDonalds and we pounded down a couple of McDoubles, because, you know, I was 22 and could do that.

We returned to the office, met the surgeon in training, and he asked where we’d been. I said, “Oh, since you were running late, the receptionist said to run and get a bite to eat or something. So we ate some cheeseburgers.”

The surgeon in training didn’t take this well. Began rubbing his balding head. He said, “Oh no, no, no, this won’t do at all. Not at all. We must reschedule.”

“Sir,” I said. “I am a manager at Blockbuster video–to get this time off–today and three more days in a row for recover–that was a feat, I tell you! Why must we reschedule?”

“You ate! You can’t eat before this. The Valium won’t work. You can take it, but it won’t work. Your cheeseburgers might get tranquilized, but you, my friend, will not.”

“But she said…” my friend Mike said gesturing to the receptionist.

“I said something like bread,” she said from behind the counter. Blue eyes, smile, blue eyes. Anger too! Oh no.

My mind scrambled. “I’ll take the pill. It’ll work. You’ll see.”

Despite his hesitation, the oral surgeon agreed. And we were off. I took the pill, went back to the room, rested in the chair, and sure enough, I began to feel something. A stirring in my brain. A numbing in my body. I knew it would work.

The procedure began. And all that something I had felt before, that numbing? It fled. Ran away. As the surgeon jacked my mouth open with some device that wouldn’t allow me to clamp down–after he numbed me–he began digging in my gums. And wisdom teeth, it turns out, don’t just come out a tooth. They come out in pieces. They are cracked and broken and jackhammered, and pieces of teeth and blood sprayed on his mask. Sweat formed on his brow.

All effects of the Valium gone, I suppose he saw something reflecting in my eyes. Horror? He brought in a second assistant. She sat down in a chair beside me and just held my hand. He brought in a woman to hold my hand! I didn’t flinch, though. I let him work. For two hours he removed slivers and chunks of gigantic teeth, but it was the roots, he said, the roots were the biggest he’d ever seen. Like the roots of a horse tooth. He brought in the beautiful receptionist and my friend Mike to look at my impressive roots.

So much pain, black smoke pouring from my mouth, but I continued on, wondering what it would be like to have real insurance.

Finally, he stopped. He took off his tooth and blood-soaked mask and said, “There is one tooth left. Upper right. I cannot do this anymore. It is too much. That tooth is not impacted. So it will remain. I cannot subject you to this anymore.”

“I can handle it,” I said around the mouth apparatus.

“You are stitched and sewn, here are two subscriptions for Vicodin. You will need them. Don’t talk or the stitching will break. Keep gauze in your mouth so clots can form. I will be here the rest of the day before returning to Denver. Call if you need anything.”

So Mike and I left. I felt particularly strong that day. Like I had done something most people hadn’t done. So I continued to play that role. I acted as if there were no pain. Of course, I filled the prescriptions. I b.s.’d with Mike, told him that’s how a man does an operation. Mike told me to stop talking. At the time I thought he was concerned I would break my stitching, in retrospect, I think he didn’t want to hear what I was saying.

I did break my stitching from talking too much. We had to go back to the oral surgeon in training that Friday afternoon. We caught him in the parking lot as he was loading up his car to head back to Denver.

“You may have to go the emergency room,” he said. “I can’t numb you. All my equipment is loaded…”

I looked at him, looked at Mike, imagine blue eyes looking at me from somewhere, and I said, “Just do it. Just stitch it. No numbing.”

He did it. And it hurt. But whatever.

I learned something that day–a fundamental lesson to my own self, to my own sense of being and history. I learned to never eat McDonalds again.

But then, these painful extractions, these lessons and formations of who we are in distinct moments, is this not what Smith meant with her epigraph: “What is past is prologue.”

What I did not know that day cost me.

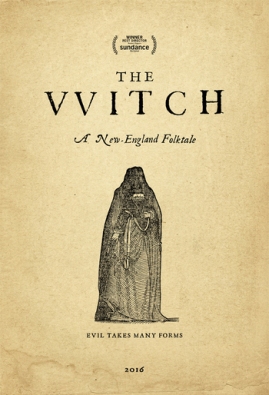

world of independent movies with the release of 2015’s horror film The Witch. Whether or not director Robert Eggers is a closet Lolly Willowes fan is not worth the debate, but the thematic core of his film is remarkably similar to Warner’s classic text. While vastly different in tone, Eggers presents his viewers with a young female protagonist named Thomasin who is the oldest daughter in a family run by a strict, puritan patriarch. Her father’s adherence to religious doctrine places Thomasin in the role of serving her family with no regard for herself. When her father decides the seventeenth-century puritan village they live in is not holy enough, he moves his small family deep into the woods to be closer to God. Instead, Thomasin and her family find themselves overcome by a series of tragic events that could be due to nature, madness, or perhaps a haunting by a witch who lives in the woods.

world of independent movies with the release of 2015’s horror film The Witch. Whether or not director Robert Eggers is a closet Lolly Willowes fan is not worth the debate, but the thematic core of his film is remarkably similar to Warner’s classic text. While vastly different in tone, Eggers presents his viewers with a young female protagonist named Thomasin who is the oldest daughter in a family run by a strict, puritan patriarch. Her father’s adherence to religious doctrine places Thomasin in the role of serving her family with no regard for herself. When her father decides the seventeenth-century puritan village they live in is not holy enough, he moves his small family deep into the woods to be closer to God. Instead, Thomasin and her family find themselves overcome by a series of tragic events that could be due to nature, madness, or perhaps a haunting by a witch who lives in the woods. So when The Witch begins with Thomasin’s father, William, delivering a speech before his friends, neighbors, and perhaps family, that he has presumably traveled from England with to start life anew, the meaning of the speech has particular relevance given Felski’s and Goodman’s context. William says in the opening of the film, “What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? . . . Was it not for the pure and faithful dispensation of the Gospels, and the Kingdom of God?” Here seems to stand a man who does not understand the method and practice of those he thought he knew. So William takes his family and moves them deep into the New England countryside to find a more pure way toward “the Kingdom of God.”

So when The Witch begins with Thomasin’s father, William, delivering a speech before his friends, neighbors, and perhaps family, that he has presumably traveled from England with to start life anew, the meaning of the speech has particular relevance given Felski’s and Goodman’s context. William says in the opening of the film, “What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? . . . Was it not for the pure and faithful dispensation of the Gospels, and the Kingdom of God?” Here seems to stand a man who does not understand the method and practice of those he thought he knew. So William takes his family and moves them deep into the New England countryside to find a more pure way toward “the Kingdom of God.”

reason I didn’t want to vote for Hillary Clinton can only boil down to one, singular fact: she is a woman. While embarrassed, humiliated (and uncertain if I even want to share this horrible story) by this fact, I am glad I figured it out. I’m glad I’m over that oppressive line of thinking, and I hope this allows me to be more introspective in the future.

reason I didn’t want to vote for Hillary Clinton can only boil down to one, singular fact: she is a woman. While embarrassed, humiliated (and uncertain if I even want to share this horrible story) by this fact, I am glad I figured it out. I’m glad I’m over that oppressive line of thinking, and I hope this allows me to be more introspective in the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.