by Simon Cropp

Understanding modernity in a literary context becomes difficult as Rita Felski notes in “Modernity and Feminism” due to “a cacophony of different and often dissenting voices” (13) trying to explain exactly what the modern is. Felski writes, “To be modern is to be on the side of progress, reason, and democracy, or, by contrast to align oneself with ‘disorder, despair, and anarchy’” (13). But this is only a piece of what modernity can be for Feslki.

Felski explains that modernity for some “comprises an irreversible historical process that includes not only the repressive forces of bureaucratic and capitalist domination but also the emergence of a potentially emancipatory, . . . self-critical, ethics of communicative reason” (13). These concepts are important in Sylvia Townsend Warner’s novel Lolly Willow’s when Laura sheds the oppressive shackles of “repressive forces” to ultimately find a kind of emancipation from the life she lived under a dominating, patriarchal rule.

Much can be said about the fact that Laura moves under the rule of another male authority– represented by Satan–when she becomes one of the witches of Great Mop. But it is also worth noting, the repressive order of Britain’s primarily male hegemonic structure no longer rules her, and Satan’s “rules” are easily understood to be much looser and more in line with Laura’s self-interests. Whatever rules he may have.

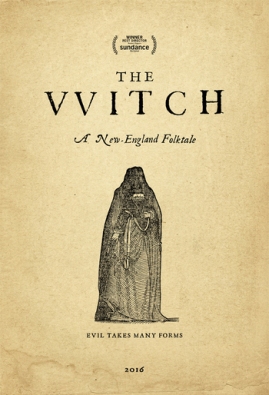

An interesting recuperation of the spirit of Warner’s story has recently occurred in the world of independent movies with the release of 2015’s horror film The Witch. Whether or not director Robert Eggers is a closet Lolly Willowes fan is not worth the debate, but the thematic core of his film is remarkably similar to Warner’s classic text. While vastly different in tone, Eggers presents his viewers with a young female protagonist named Thomasin who is the oldest daughter in a family run by a strict, puritan patriarch. Her father’s adherence to religious doctrine places Thomasin in the role of serving her family with no regard for herself. When her father decides the seventeenth-century puritan village they live in is not holy enough, he moves his small family deep into the woods to be closer to God. Instead, Thomasin and her family find themselves overcome by a series of tragic events that could be due to nature, madness, or perhaps a haunting by a witch who lives in the woods.

world of independent movies with the release of 2015’s horror film The Witch. Whether or not director Robert Eggers is a closet Lolly Willowes fan is not worth the debate, but the thematic core of his film is remarkably similar to Warner’s classic text. While vastly different in tone, Eggers presents his viewers with a young female protagonist named Thomasin who is the oldest daughter in a family run by a strict, puritan patriarch. Her father’s adherence to religious doctrine places Thomasin in the role of serving her family with no regard for herself. When her father decides the seventeenth-century puritan village they live in is not holy enough, he moves his small family deep into the woods to be closer to God. Instead, Thomasin and her family find themselves overcome by a series of tragic events that could be due to nature, madness, or perhaps a haunting by a witch who lives in the woods.

This concept of Puritan developments in the seventeenth-century becoming too big, too modern, is not something only believed by Thomasin’s father.

In her article “The Puritan Cosmopolis: A Covenantal View,” Nan Goodman writes about recent scholarship on Puritan globalism “that defined English sovereignty in this period and that characterized the colonization and imperialism inherent in the Puritans’ settlements in New England” (4). Compare this concept of Puritan globalism to Felski’s expanded notions on modernity. Feslki writes, “On the other hand, the idea of the modern was deeply implicated from its beginnings with a project of domination over those seen to lack this capacity for reflective reasoning. In the discourses of colonialism, for example, the historical distinction between the modern present and the primitive past was mapped onto the spatial relations between Western and non-Western societies” (14). Colonialism has a long history in the United States, and despite commonly held views that Puritans retreated from the modernizing of the world, the opposite is perhaps true in the sense that Puritans used the modernizing of the world for their own proselytizing.

So when The Witch begins with Thomasin’s father, William, delivering a speech before his friends, neighbors, and perhaps family, that he has presumably traveled from England with to start life anew, the meaning of the speech has particular relevance given Felski’s and Goodman’s context. William says in the opening of the film, “What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? . . . Was it not for the pure and faithful dispensation of the Gospels, and the Kingdom of God?” Here seems to stand a man who does not understand the method and practice of those he thought he knew. So William takes his family and moves them deep into the New England countryside to find a more pure way toward “the Kingdom of God.”

So when The Witch begins with Thomasin’s father, William, delivering a speech before his friends, neighbors, and perhaps family, that he has presumably traveled from England with to start life anew, the meaning of the speech has particular relevance given Felski’s and Goodman’s context. William says in the opening of the film, “What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, kindred, our fathers’ houses? We have travailed a vast ocean. For what? For what? . . . Was it not for the pure and faithful dispensation of the Gospels, and the Kingdom of God?” Here seems to stand a man who does not understand the method and practice of those he thought he knew. So William takes his family and moves them deep into the New England countryside to find a more pure way toward “the Kingdom of God.”

Soon puritanical madness overtakes the family, and because Thomasin is on the verge of womanhood, the family turns on her and believes she has made a pact with Satan. That she has become a witch herself. As viewers, we know this to be untrue, and if the images on the screen are to be trusted, we know a witch in the woods is causing the family’s torment. Thomasin behaves exactly as a young woman of her time is supposed to behave. She takes care of children, cooks, cleans, prays, and does everything the hegemonic order of her community has asked.

At one point in the film, her father—who seems to be her only true ally in the family—suggests to her mother that they take her back to the village and marry her off. That her problems will be fixed by this solution.

The mother’s anger wins the father over though, and they decide Thomasin is a witch, though the film clearly depicts her as innocent. Dutiful, good-natured, kind-hearted. Everything she has been raised to be. It seems as if her fate will be to be burned as a witch though she clearly is not one at all.

Ultimately tragedy befalls the entire family, and Thomasin learns there is a witch in the woods, but worse, Satan has been on their property the entire time hiding amidst their livestock. He has been watching her suffer at the hands of her family, and in the end, he takes a human form and offers her freedom from the oppressive control of her community. All she has to do is sign his book, or consent to his rule, become a witch, like the other witches that have been in the woods all along.

Thomasin takes him up on his offer, and the film ends with her gleeful laughter as she leaves Satan behind and joins a coven of witches around a fire. Finally, she is free from the oppressive rule of her society.

.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.